Monthly Corner

IDH Publication, 2026

Gender-Based Violence (GBV) is not just a social issue, it’s a systemic challenge that undermines agricultural value chains.

In rural and isolated areas, GBV threatens women’s safety, limits their economic participation, and weakens food security. When women cannot work safely, entire communities lose resilience, and businesses lose productivity. Climate resilience strategies that overlook gendered risks leave communities exposed and women vulnerable.

Ending GBV is essential for building equitable, sustainable, and climate-resilient agri-food systems; and it’s not only a human rights imperative, but also central to climate adaptation and economic stability.

The good news? Solutions work. Programs like the Women’s Safety Accelerator Fund (WSAF) demonstrate that addressing GBV can enhance productivity and strengthen workforce morale and brand reputation. Safe, inclusive workplaces aren’t just good ethics, they’re smart business.

Gurmeet Kaur Articles

Luc Barriere-Constantin Article

This article draws on the experience gained by The Constellation over the past 20 years. It is also a proposal for a new M&E and Learning framework to be adopted and adapted in future projects of all community-focused organisations.

Devaka K.C. Article

Sudeshna Sengupta Chapter in the book "Dialogues on Development edited by Prof Arash Faizli and Prof Amitabh Kundu."

Events

Vacancies

- We’re Hiring: National Evaluation Consultant – Bangladesh

UN Women is recruiting a National Evaluation Consultant (Bangladesh) to support the interim evaluation of the Joint Regional EmPower Programme (Phase II).

This is a great opportunity to work closely with the Evaluation Team Leader and contribute to generating credible, gender-responsive evidence that informs decision-making and strengthens programme impact.

📍 Location: Dhaka, Bangladesh (home-based with travel to project locations)

📅 Apply by: 24 February 2026, 5:00 PM

🔗 Apply here: https://lnkd.in/gar4ciRr

If you are passionate about feminist evaluation, gender equality, and rigorous evidence that drives change (or know someone who is) please apply or share within your networks.

- Seeking Senior Analyst - IPE Global

About the job

IPE Global Ltd. is a multi-disciplinary development sector consulting firm offering a range of integrated, innovative and high-quality services across several sectors and practices. We offer end-to-end consulting and project implementation services in the areas of Social and Economic Empowerment, Education and Skill Development, Public Health, Nutrition, WASH, Urban and Infrastructure Development, Private Sector Development, among others.

Over the last 26 years, IPE Global has successfully implemented over 1,200 projects in more than 100 countries. The group is headquartered in New Delhi, India with five international offices in United Kingdom, Kenya, Ethiopia, Philippines and Bangladesh. We partner with multilateral, bilateral, governments, corporates and not-for-profit entities in anchoring development agenda for sustained and equitable growth. We strive to create an enabling environment for path-breaking social and policy reforms that contribute to sustainable development.

Role Overview

IPE Global is seeking a motivated Senior Analyst – Low Carbon Pathways to strengthen and grow its Climate Change and Sustainability practice. The role will contribute to business development, program management, research, and technical delivery across climate mitigation, carbon markets, and energy transition. This position provides exceptional exposure to global climate policy, finance, and technology, working with a team of high-performing professionals and in collaboration with donors, foundations, research institutions, and public agencies.

Measuring Social Norms on WEE Programmes: Lessons from Itad’s Work in Gender Equality

The role of social norms change in economically empowering women was a hot topic at the SEEP Women’s Economic Empowerment Global Learning Forum earlier this year.

The event was opened by Professor Naila Kabeer, who argued that not taking cultural and social norms into consideration when enhancing women’s economic empowerment (WEE) can undermine the transformative potential of WEE efforts. Dr Cynthia Drakeman also presented the second report from the UN High Level Panel on WEE. One of the key recommendations from this report was to address the norms perpetuating violence, stigmatisation of informal labour, and gendered roles and abilities.

With this growing consensus that to advance women’s agency programmes have to delve deeper into the social norms that limit women’s participation in the economy, comes a clear need for guidance on how to measure these changes. We need to be able to do this in order prove what works, and to improve WEE programme design. Some of the best practice emerging in this area includes:

- We know that changes in norms, attitudes and behaviours are difficult to fully understand with quantitative data alone. We need to use mixed research methods – both qualitative and quantitative research. Oxfam have developed guidance for combining qualitative focus group discussions and house hold surveys to measure changes in social norms around unpaid care work on its WE-CARE programme.

- It is important to use participatory methods, exemplified in by the BEAM exchanges tools and methodology in this case study, and the participatory videos used by CARE on their POWER programme to measure social norm changes around women’s financial inclusion in this case study.

- Capture more than just women’s perceptions by interviewing men and boys as well, as exemplified in the BEAM Exchange case study on Making Markets Work for the Chars (M4C)....

But, these practices and tools are still in their early stages, and there is room to continue developing our understanding in this area. To add to the discussion, Itad can offer lessons from our work in monitoring and evaluating social norms programmes, such as Voices for Change (V4C).

V4C is a DFID-funded programme in Nigeria which aims to create a stronger enabling environment for girls and women. Itad is one of the four partners in the consortium managing V4C for DFID and we are leading on the ‘results’ component.

To measure changes in social norms, we use a mixed methods approach, which includes an annual quantitative panel survey to explore people’s attitudes and typical behaviours. The panel is made up of a representative sample of our target group; 4,798 young people. This is complemented by focus groups and interviews with key influencers to explore how and why target norms exist.

V4C offers two frameworks that could be used for measuring social norm change on WEE programmes; an empirical and normative matrix, and an action and attitude matrix.

- Using the empirical and normative matrix to design data collection tools and analyse data

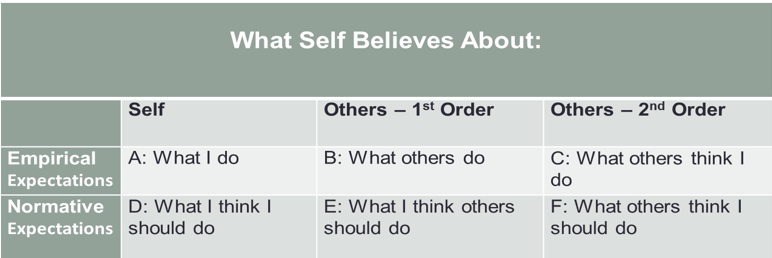

Social norms are a pattern of behaviour that people conform to because they believe that their reference group (people important to them) conforms to it (empirical expectation), and because their reference group believes that they ought to conform to it (normative expectation). The empirical and normative matrix (Based on Gerry Mackie et al. 2015) outlines dimensions of social norms based on this definition.

For each social norm a programme wants to track, the empirical and normative matrix can be used to design data collection tools by guiding multi-dimensional lines of enquiry. The matrix allows us to track changes in both the practices (what people do here and now) and attitudes of individuals, as well as the perceived practices and attitudes of communities, which can be used to pin point where changes are needed. Tracking all of these dimensions of social norms allows programmes to design or adapt interventions accordingly.

For example, imagine we are tracking changes in the social norms around married women leaving their houses to access mobile money outlets. Collecting data against the six dimensions in the matrix for social norms around mobility, and mapping it against this matrix, would tell us whether or not there is a public tolerance of women’s mobility (F, E), whether or not women are mobile (A, B), and personal attitudes towards mobility (D, E). The data from this can be used to design or adapt an intervention by showing us in which cases we need to shift public attitudes (where data collection shows a low public tolerance), or whether to investigate other barriers to mobility (where data collection shows high tolerance but low practice).

Diagram 1: Empirical and Normative Matrix

2. Using an Attitude and Action matrix to track social norms change

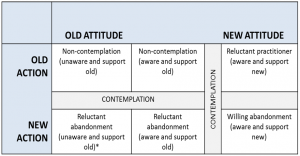

This tool is useful to track and compare changes for different groups; geographic, demographic, age etc. It is based on the assumption that changing a social norm requires individuals to go through three changes – gaining knowledge, changing their attitudes, and changing their actions (though change does not always have to happen in that order). This framing helps programmes in using their data to track where different groups are in this transition in order to monitor progress and pin point constraints for intervention design.

Diagram 2: Attitude and Action Matrix

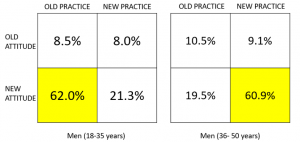

Diagram 3: Results in an Attitude and Action Matrix

Diagram 3 shows how we can map out results for different groups using the attitude and action matrix (diagram 2), which helps to paint a picture of how best to design and adapt interventions. Using our mobile money example from above, imagine the results in diagram 3 are the results from a survey on the six dimensions of the empirical and normative matrix for social norms around married women leaving their husband’s house. Analysing the results in this way now allows us to see that most younger men have new attitudes but not new practices, whilst most older men have both new attitudes and new practices. We can use this information to adapt our programme by enlisting older male champions to spread awareness of their new practices and encourage younger men to do the same.

Where do we go from here to build experience of measuring change in social norms which affect women’s economic empowerment? We clearly need further experimentation and Itad would welcome opportunities to adapt and apply the two analytical frameworks described above. Critically, we would need to find ways to generate data rapidly so we can get a feel of whether WEE interventions are working to shift social norms early on.

For more information on Itad’s work measuring social norm change, click here.

Add a Comment

-

Comment by Paulina Lawsin on September 5, 2017 at 14:33

-

Interesting post Mollie. I admit there are terms that I need to learn more about and have to take a second and third look at the tools. Will definitely refer to it when we conduct tracking on social norms in our project area.

-

Comment by Paloma Lafuente Gómez on August 2, 2017 at 12:11

-

Fantastic post, thanks a lot for sharing.

© 2026 Created by Rituu B Nanda.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of Gender and Evaluation to add comments!

Join Gender and Evaluation